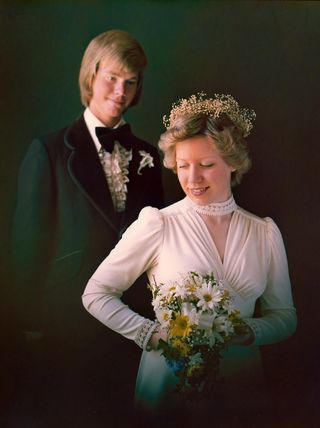

Brad Anderson never guessed that he'd meet the love of his life as a junior in high school while washing dishes at a department store cafeteria. But there she was: LuAnne, who bussed tables, had similar family values and was easy to talk to. Plus, she was cute. "She looked good in her bussing costume, that's for sure," Anderson, now 60, says.

With the exception of a brief split in high school — Anderson won her back with a box of chocolates — they've been together ever since. They've lived in Nebraska for the last 26 years and have two kids: Ian, now 36, and Hannah, now 32. The couple loved to go Irish dancing together — sometimes four to five times a week — and LuAnne taught dance on the side.

But around 2003, LuAnne's personality and behavior started to change, and her memory became faulty. When a former dance student she knew well came to visit after only being away for a year, LuAnne greeted her by saying, "Hi. I'm LuAnne. Who are you?"

And then, in 2009, LuAnne pointed to a sparrow and said, "What's that?"

"I just stopped cold," Anderson says. "I didn't even know how to respond."

The Diagnosis

In July 2010, at the age of 55, LuAnne was diagnosed with semantic dementia, a condition that's similar to Alzheimer's disease in that it slowly kills brain cells.

"I was numb. I didn't know what it meant. I was clueless," Anderson says. "But I could tell from the way the nurses were talking that it was something I'd need to dive into quickly and learn about."

An MRI showed atrophy in the temporal lobe of LuAnne's brain — the part that controls memory, speech, and comprehension — and psychological testing showed her brain function was all over the place.

LuAnne was losing the ability to assign meaning to words, and the diagnosis meant that would only get worse. Her ability to read, spell, talk, and recognize faces would decline, as well as her empathy — her ability to understand the emotions of others. Doctors told Brad that once the diagnosis is made, people generally live only four to eight more years. The exact cause of semantic dementia is unknown, but it may be due to a mix of genetic, medical, and lifestyle factors.

Anderson tried explaining the diagnosis to LuAnne, but she couldn't fully understand what was happening to her.

"She was never sad. I never saw her cry," Anderson says. "But she would get angry and frustrated. She'd say things like, 'The doctors aren't helping me.'"

And she had a point: There was only so much the doctors could do to help her. They gave her medications that were designed to either boost her cognition or manage her mood, but no drug could slow the progression of the disease.

Reversing Roles

Shortly after the diagnosis, LuAnne was forced to medically retire from her job as a business manager at a university. Work had become too difficult for her. She had to print out every email that she received and run her finger under each word to try to understand what it said before replying. She was also having trouble recognizing coworkers.

Anderson was thrust headfirst into the role of LuAnne's caregiver without much preparation or warning, as is the case for many spouses of people with dementia.

"We know that about 70 percent of people with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias are cared for at home by their spouse or other family members or friends," says Ruth Drew, MS, LPC, director of family and information services at the Alzheimer's Association.

Being a caregiver is no easy task: In 2015, more than 15 million caregivers provided an estimated 18.1 billion hours of unpaid care. Nearly 60 percent of Alzheimer's and dementia caregivers rate the emotional stress of caregiving as high or very high, and 74 percent are somewhat to very concerned about maintaining their own health.

At first, Anderson wasn't sure how he would navigate this new maze. He needed to keep his job in telecommunications and data communications so they'd have health insurance and income, but he also needed to care for LuAnne. The worst part? The one person whom Anderson desperately wanted to talk to about all of the caregiving decisions was the one person he couldn't communicate with.

The Alzheimer's Association paired him with a lawyer who specialized in elder law to help him figure out how to pay for LuAnne's care. For a couple of years, LuAnne was well enough to be on her own at home during the day while Anderson was at work. But as time went on, she needed more supervision.

When taking care of her, Anderson's head was always on a swivel, as if he were caring for a young child. One day, he pointed to a garter snake in the yard and she reached down and grabbed it. Eventually Anderson had to take the car keys away and hire professional caregivers to help care for her in the afternoons, because she usually slept until noon.

One morning, before the caregivers arrived and while Anderson was at work, LuAnne got up earlier than usual and became manic. She left the house, hopped on a bus, and was heading downtown to a bank so she could buy herself a car and get back some of her independence.

Fortunately, Anderson had set up video cameras in the house and could keep track of her location remotely via GPS because she always carried an iPad with her, so he left work immediately and caught her as she was exiting the bus. When the bus door opened, she looked at Anderson and said, "Who are you?"

"Everywhere she goes, she's around strangers," Anderson says. "Even me."

Around that time, LuAnne also started making suicidal statements, like, "Oh, I'll just go jump in front of a car." At that point, Anderson knew that she needed more help than he or the caregivers could provide, so he placed her in a nursing home in Omaha, about an hour away from their house in Lincoln.

Seeking Comfort

Sometimes people will say to Anderson: "It's great that you're taking such good care of your wife." Many are surprised to see a man in the caregiving role because about two thirds of caregivers are women, but Anderson isn't fazed.

"My thought is: Well, what else would I be doing? Maybe it's old-fashioned, but I made a promise to LuAnne when we got married and I'm doing my best to honor that," he says.

With help from the Alzheimer's Association, Anderson founded a support group for men who are caregivers, which has helped him feel less alone.

"It's so beneficial to just be someplace where you can talk to other people and you never have to explain," he says. "They understand."

Drew, who has counseled many male and female caregivers, says that support groups are vital, especially for male caregivers.

"Sometimes female caregivers find it easier to talk about what they're dealing with and may already have a network of people that they can share with, but for men, that can sometimes be harder," she says. "It's so important to talk through these issues. There's so much to figure out — it can be overwhelming. I'd encourage any man or woman who is dealing with all of the adjustments of being a caregiver to seek out a support group.

Anderson addition to his support group, Anderson has found comfort in writing poetry. One day, he started recording his thoughts and, to his surprise, they turned into verses.

"When I started writing poetry, it was because I didn't know how to express what I was feeling," says Anderson.

He read one poem aloud at a recent community health event and participated in the Alzheimer's Association's The Longest Day campaign by writing "The Longest Poem" to raise money for dementia research. Here's an excerpt:

Forgetting the woman you became

Unlearning the person you were

Slowly at first, imperceptible

A name, a face, a family friend

Shadow dancing with who you were

Caring for the person you are

The dance has changed, the caller is new

Our love remains unchanged

Living in the Present

Today, LuAnne can say only two words: "Oh, gosh." She says them over and over with a different inflection each time, as if she's trying desperately to communicate her feelings but can't find the words. If she's not in bed, she's in a wheelchair, because her physical capabilities have deteriorated. Anderson visits her three or four times a week.

When he walks into her room at the nursing home, she starts laughing. She'll reach out and pull him in for a kiss or hug. "How she knows me, I don't know," Anderson says. "I think that goes beyond cognitive thought. There's something else at work. She knows that I'm important. A lot of people talk about the heart being a thinking organ. Maybe it does more than we realize."

There isn't much they can do together. Anderson will sit next to her and help her play a jigsaw puzzle game on her iPad. Or they'll go sit in the nursing home's garden. Or he'll sit in front of her so they're face-to-face and simply hold her while Irish music plays in the background.

Anderson admits that facing this is sometimes too much to bear. "We've been married 41 years. When you've been with someone that long, you feel like you're losing your partner in crime, the person you did everything with."

The most valuable lesson he's learned came from the caregivers at LuAnne's nursing home.

"The people caring for her did not know her before. All they know is who she is now, and they all love her," Anderson says. "They're not mourning or missing her or looking for the person she used to be. And that was the single most helpful thing for me — to stop thinking about what's lost and be present with where she is now. I need to appreciate the time I do have with her now. I've learned how to keep those types of sad thoughts in a little compartment."

Read the full version of "The Longest Poem" here. To find a caregiver support group in your area and get more information about dementia, visit the Alzheimer's Association's website at alz.org

Correction: July 12, 2016. An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated Brad Anderson's profession. He currently works in telecommunications and data communications, not on electronic equipment for railroad signals.